Screengrab - This Is This

(Or the Strange Case of Michael Cimino)

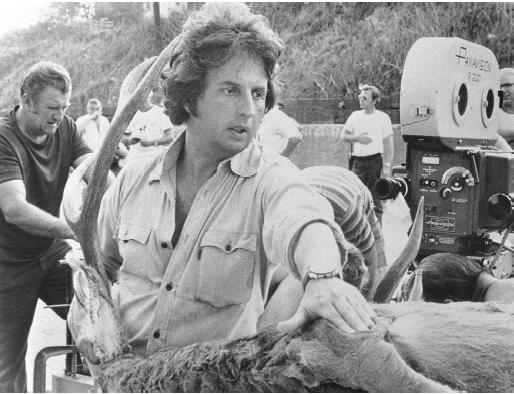

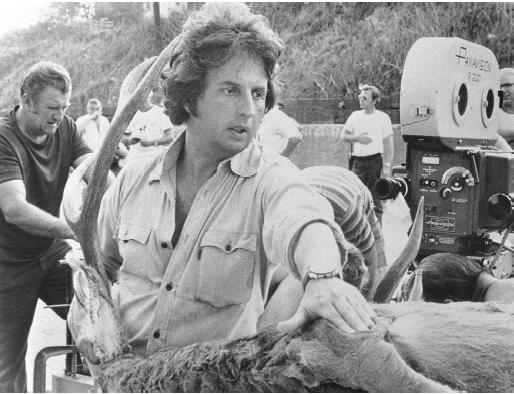

No American Director has ever fallen the way Michael Cimino did. In a way, that was only fitting, because his rise had been just as sudden and startling. Having co-written the screenplays for two middling but interesting 70s genre films, Silent Running and Magnum Force (the latter with John Milius), Cimino's script for Thunderbolt and Lightfoot was purchased by Clint Eastwood, who intended to direct and star in it himself. Cimino persuaded Eastwood to allow him to direct it and the film, a peculiar little heist story, was a hit - Jeff Bridges was even Oscar nominated for his role - and Cimino was suddenly a player. For his next film, the extraordinarily ambitious tale of the effect of the Vietnam War on a group of Pennsylvania Steelworkers, Cimino gathered a starry cast, a sizeable budget and the trust of a major studio.

Has any director ever trumped "difficult second album syndrome" quite so effectively? The Deer Hunter is a Great Film, one of the best of the decade, perhaps one of the greatest American films ever made. It was an immediate Critical and commercial success, it won 5 Oscars - including Best Film and Best Director - and it gave Cimino a clout most of his peers could only dream of. Ever ambitious, he decided to use that clout to make a massive Western which was really a Marxist history of the Johnson County Wars, and indeed of the American expansion into the West itself. Heavens Gate would cost $40 million, the equivalent of $107 million today, come in months behind schedule, and prove a resounding flop, both with audiences and critics. Cimino's original cut was over 5 hours long, but United Artists forced him to cut that down to 219 minutes for its premiere at the New York Film Festival, where it was eviscerated by critics. The film was again subjected to editing and the version eventually released was only 149 minutes long and barely coherent. It earned $1.8 million at the American Box Office. The financial fallout of this failure led to the demise of United Artists itself.

Cimino moved on, though his reputation had suffered such damage that no Hollywood Studio would involve itself with him, and five years after the 1980 release of Heavens Gate he was forced to finance his next film, The Year of the Dragon, independently. It was a commercial success but didn't fare quite so well with critics, and his next effort, The Sicilian, was an outright failure. In the 20 years since he has made only two films (Desperate Hours and Sunchaser), both of them unmemorable and lacking any evidence of the involvement of the singular talent responsible for The Deer Hunter. He lives in Paris, has published a novel, and is still the subject of numerous Hollywood rumours, including tales of madness and sex changes. From Oscar Winning Wonderkid to exiled has-been in a few decades is an impressive decline by any standards. But at least Cimino has left a legacy to be proud of.

Momentarily leaving aside The Deer Hunter, the two films that bookend it both have their admirable qualities. Thunderbolt and Lightfoot is perhaps the quirkiest film Clint Eastwood made in the 1970s, a buddy movie comedy-drama, made with uncommon confidence and sureness of tone by a debuting director. If Cimino used it as a sort of film school - and he has spoken at length of his admiration for and gratitude to Eastwood - then he learned his lessons well, because the leap between it and his two subsequent films is enormous. Heavens Gate has been re-evaluated in the decades since its original release. A screening of its 219 minute cut on the American cable channel the Z-Channel in the mid-80s was met with some approving reviews, echoing the noises coming from France, where the film had a strong following among Film critics.

Steven Bach, an executive at United Artists throughout the films production, wrote a fascinating book called "Final Cut" about the experience, painting an extremely unflattering portrait of Cimino as a pretentious egotist in the process. But the film was released in the 219 minute "Directors" Cut on VHS in the mid-80s, arguably beginning the trend for Directors Cuts that has flourished on DVD in recent years, and its critical reputation is perhaps higher now than at any time since its release. It is a terribly flawed film, but its spectacle and beauty are exhilarating, as is Cimino's insane ambition. His canvas is massive (you can see much of that colossal budget on screen), and he needs big movie stars to carry the story through its long running time and more involved political stretches. Instead he cast character actors like Kris Kristofferson and Isabelle Huppert, who, fine actors as they are, are incapable of shouldering the burden of a film as huge as this. Cimino, as Bach's book suggests, was also far too in love with his own material and his vision, and, unwilling to compromise, he allows longeurs to settle over too many scenes, so that some stretches of the film are unforgiveably boring. But it is all stunningly shot, and some of the set-piece sequences are brilliant. An indication of how problematic many aspects of the film are is the nature of that beauty itself - Cimino and his Cinematographer Vilmos Zsigmond are so enamoured of many of their perfectly lit, finely composed set-ups that it seems the film is reluctant to cut away from them at all. The viewer is invited to luxuriate in them and marvel at their beauty, at the expense of the narrative. This is the very definition of self-indulgence. But though Cimino may have taken himself too seriously, that is partly what is awesome about the film - it is ambitious enough to regard itself as a work of art, and though it fails on many levels, there is something glorious about that failure.

That leaves The Deer Hunter as Cimino's greatest achievement. Taking something from The Best Years of Our Lives, William Wyler's 1946 Oscar-winning melodrama about 3 soldiers returning to their smalltown lives from the Second World War and the changes and problems they encounter, Cimino fashions a humanist epic, full of vivid, recognisable characters and relationships. The film works so well as a drama that on a first viewing it is difficult to discern its thematic concerns. The characters - a group of friends revolving around the core of Michael ( Robert DeNiro), Steven (John Savage) and Nick (Christopher Walken) - and the story - the days before their departure to fight in Vietnam, some of what befalls them there, and the consequences - involve the audience for all of the three hour running time, making the ending emotionally shattering. But it is a rich, layered film, the kind of experience that offers something new on every viewing. Its first hour, which seems to drift plotlessly through a (shotgun) Wedding and the ensuing party, patiently introducing characters and painting in their personalities, subtly outlining the tensions crackling between them, is utterly masterful and seamless. David Thompson has written that it prompts the viewer to think "where is this film taking me, and why am I going with it?"

One of Cimino's major themes is the idea of ritual and as such the film is full of them - a Wedding, the dances at the Wedding party, hunting trips, men drinking together after work, a funeral, people gathered to gamble. He seems also interested in structure and The Deer Hunter toys with cinematic norms, just as Thunderbolt & Lightfoot had in its own way. The sudden jumpcut from a quiet, sombre scene where John (George Dzunda) plays Chopin on the piano in his bar and the men listen in silence to the roar of a Vietnamese battlefield is probably the best example of this, serving as it does to signal the end of the films first act and the shift of gears into the second. That second act is an awesome piece of filmaking, and was the most controversial element of the film upon its initial release. But The Deer Hunter has remained in the popular consciousness because of the Russian Roulette sequence, which is central to the second act, and is an amazingly tense, agonising scene, superbly shot, edited and acted for maximum impact.

The sadness and regret of the third act - where the characters struggle with what has happened to their lives and their country - is the only ending such a story can really allow. It is a modern epic, encompassing much of the reality of life in the late 20th Century, and perhaps the best depiction of a group of working class friends in any film from its era. It is also many stories in one - a love story, a story of friendship, of the cost of war, of community. Pauline Kael damned it at the time of its release as "Beau Geste goes-to-Vietnam" and she was right, but that seems to me to be high praise. Because it is an adventure story as much as anything else, and it is a truly great adult adventure story.

The passage that I love most in The Deer Hunter is the hunting sequence that follows the Wedding Party night. The men drive into the mountains and squabble when they arrive, hungover, and discover that Stan (John Cazale) has forgotten his boots. He and Michael argue, and the importance of the hunt to Michael is underlined, along with something of his solitude, his apartness from the others, his discipline. These are the qualities that will ultimately allow him to survive in Vietnam. Until this moment it has been a film abubble with humanity - the roar and clatter of the Refinery, the clamour of a bar, the ceremony of the Wedding, the raucousness of the party. The argument in the mountains is another scene intent upon the people, their humanity and the tensions between them. Suddenly Cimino cuts to a shot of a hunting lodge upon a mountain and his camera follows Michael and Nick as they emerge in the cold grey light of dawn. Choral music rises on the Soundtrack and Walken's silhouette is picked out as he crests a hill and is reflected in a small lake below, his oddly graceful dancer's movements unmistakeable. He and DeNiro are silent on their hunt, which climaxes when DeNiro takes down a deer with his "one shot". We hear that shot and see the deer fall and quiver and die as the music arrives at a crescendo. It is a rare scene of pure natural beauty in the film, and it feels somehow transcendent, blessed by the death of the animal, which seems to presage all of the death and pain to come. A few moments later the film and the characters are in Vietnam, and all is different.

On the basis of The Deer Hunter, Cimino seems like a visionary, more than the equal of other giants of his generation like Coppola and Scorsese. But then he could never sustain such a level, and it seems that the film was a one-off, a uniquely beautiful and perfectly-formed work. The pity of it is that since Heavens Gate, not one of his films has even seemed to have been made by the same man. The best of the four, Year of the Dragon, is an exploitative cop thriller based on an Oliver Stone script and almost parodic in its lack of originality, dredging up of cliches, nastiness and borderline racism. The other three could almost have been made by any journeyman director, so lacking are they in any real personality or sense of vision.

Which raises the question : what could have happened to Cimino? How can such talent simply disappear?

Perhaps its far simpler than that. Perhaps he knew he could never equal The Deer Hunter after his only real attempt, Heavens Gate, almost ruined him. Perhaps he gave up. Who could blame him?

No American Director has ever fallen the way Michael Cimino did. In a way, that was only fitting, because his rise had been just as sudden and startling. Having co-written the screenplays for two middling but interesting 70s genre films, Silent Running and Magnum Force (the latter with John Milius), Cimino's script for Thunderbolt and Lightfoot was purchased by Clint Eastwood, who intended to direct and star in it himself. Cimino persuaded Eastwood to allow him to direct it and the film, a peculiar little heist story, was a hit - Jeff Bridges was even Oscar nominated for his role - and Cimino was suddenly a player. For his next film, the extraordinarily ambitious tale of the effect of the Vietnam War on a group of Pennsylvania Steelworkers, Cimino gathered a starry cast, a sizeable budget and the trust of a major studio.

Has any director ever trumped "difficult second album syndrome" quite so effectively? The Deer Hunter is a Great Film, one of the best of the decade, perhaps one of the greatest American films ever made. It was an immediate Critical and commercial success, it won 5 Oscars - including Best Film and Best Director - and it gave Cimino a clout most of his peers could only dream of. Ever ambitious, he decided to use that clout to make a massive Western which was really a Marxist history of the Johnson County Wars, and indeed of the American expansion into the West itself. Heavens Gate would cost $40 million, the equivalent of $107 million today, come in months behind schedule, and prove a resounding flop, both with audiences and critics. Cimino's original cut was over 5 hours long, but United Artists forced him to cut that down to 219 minutes for its premiere at the New York Film Festival, where it was eviscerated by critics. The film was again subjected to editing and the version eventually released was only 149 minutes long and barely coherent. It earned $1.8 million at the American Box Office. The financial fallout of this failure led to the demise of United Artists itself.

Cimino moved on, though his reputation had suffered such damage that no Hollywood Studio would involve itself with him, and five years after the 1980 release of Heavens Gate he was forced to finance his next film, The Year of the Dragon, independently. It was a commercial success but didn't fare quite so well with critics, and his next effort, The Sicilian, was an outright failure. In the 20 years since he has made only two films (Desperate Hours and Sunchaser), both of them unmemorable and lacking any evidence of the involvement of the singular talent responsible for The Deer Hunter. He lives in Paris, has published a novel, and is still the subject of numerous Hollywood rumours, including tales of madness and sex changes. From Oscar Winning Wonderkid to exiled has-been in a few decades is an impressive decline by any standards. But at least Cimino has left a legacy to be proud of.

Momentarily leaving aside The Deer Hunter, the two films that bookend it both have their admirable qualities. Thunderbolt and Lightfoot is perhaps the quirkiest film Clint Eastwood made in the 1970s, a buddy movie comedy-drama, made with uncommon confidence and sureness of tone by a debuting director. If Cimino used it as a sort of film school - and he has spoken at length of his admiration for and gratitude to Eastwood - then he learned his lessons well, because the leap between it and his two subsequent films is enormous. Heavens Gate has been re-evaluated in the decades since its original release. A screening of its 219 minute cut on the American cable channel the Z-Channel in the mid-80s was met with some approving reviews, echoing the noises coming from France, where the film had a strong following among Film critics.

Steven Bach, an executive at United Artists throughout the films production, wrote a fascinating book called "Final Cut" about the experience, painting an extremely unflattering portrait of Cimino as a pretentious egotist in the process. But the film was released in the 219 minute "Directors" Cut on VHS in the mid-80s, arguably beginning the trend for Directors Cuts that has flourished on DVD in recent years, and its critical reputation is perhaps higher now than at any time since its release. It is a terribly flawed film, but its spectacle and beauty are exhilarating, as is Cimino's insane ambition. His canvas is massive (you can see much of that colossal budget on screen), and he needs big movie stars to carry the story through its long running time and more involved political stretches. Instead he cast character actors like Kris Kristofferson and Isabelle Huppert, who, fine actors as they are, are incapable of shouldering the burden of a film as huge as this. Cimino, as Bach's book suggests, was also far too in love with his own material and his vision, and, unwilling to compromise, he allows longeurs to settle over too many scenes, so that some stretches of the film are unforgiveably boring. But it is all stunningly shot, and some of the set-piece sequences are brilliant. An indication of how problematic many aspects of the film are is the nature of that beauty itself - Cimino and his Cinematographer Vilmos Zsigmond are so enamoured of many of their perfectly lit, finely composed set-ups that it seems the film is reluctant to cut away from them at all. The viewer is invited to luxuriate in them and marvel at their beauty, at the expense of the narrative. This is the very definition of self-indulgence. But though Cimino may have taken himself too seriously, that is partly what is awesome about the film - it is ambitious enough to regard itself as a work of art, and though it fails on many levels, there is something glorious about that failure.

That leaves The Deer Hunter as Cimino's greatest achievement. Taking something from The Best Years of Our Lives, William Wyler's 1946 Oscar-winning melodrama about 3 soldiers returning to their smalltown lives from the Second World War and the changes and problems they encounter, Cimino fashions a humanist epic, full of vivid, recognisable characters and relationships. The film works so well as a drama that on a first viewing it is difficult to discern its thematic concerns. The characters - a group of friends revolving around the core of Michael ( Robert DeNiro), Steven (John Savage) and Nick (Christopher Walken) - and the story - the days before their departure to fight in Vietnam, some of what befalls them there, and the consequences - involve the audience for all of the three hour running time, making the ending emotionally shattering. But it is a rich, layered film, the kind of experience that offers something new on every viewing. Its first hour, which seems to drift plotlessly through a (shotgun) Wedding and the ensuing party, patiently introducing characters and painting in their personalities, subtly outlining the tensions crackling between them, is utterly masterful and seamless. David Thompson has written that it prompts the viewer to think "where is this film taking me, and why am I going with it?"

One of Cimino's major themes is the idea of ritual and as such the film is full of them - a Wedding, the dances at the Wedding party, hunting trips, men drinking together after work, a funeral, people gathered to gamble. He seems also interested in structure and The Deer Hunter toys with cinematic norms, just as Thunderbolt & Lightfoot had in its own way. The sudden jumpcut from a quiet, sombre scene where John (George Dzunda) plays Chopin on the piano in his bar and the men listen in silence to the roar of a Vietnamese battlefield is probably the best example of this, serving as it does to signal the end of the films first act and the shift of gears into the second. That second act is an awesome piece of filmaking, and was the most controversial element of the film upon its initial release. But The Deer Hunter has remained in the popular consciousness because of the Russian Roulette sequence, which is central to the second act, and is an amazingly tense, agonising scene, superbly shot, edited and acted for maximum impact.

The sadness and regret of the third act - where the characters struggle with what has happened to their lives and their country - is the only ending such a story can really allow. It is a modern epic, encompassing much of the reality of life in the late 20th Century, and perhaps the best depiction of a group of working class friends in any film from its era. It is also many stories in one - a love story, a story of friendship, of the cost of war, of community. Pauline Kael damned it at the time of its release as "Beau Geste goes-to-Vietnam" and she was right, but that seems to me to be high praise. Because it is an adventure story as much as anything else, and it is a truly great adult adventure story.

The passage that I love most in The Deer Hunter is the hunting sequence that follows the Wedding Party night. The men drive into the mountains and squabble when they arrive, hungover, and discover that Stan (John Cazale) has forgotten his boots. He and Michael argue, and the importance of the hunt to Michael is underlined, along with something of his solitude, his apartness from the others, his discipline. These are the qualities that will ultimately allow him to survive in Vietnam. Until this moment it has been a film abubble with humanity - the roar and clatter of the Refinery, the clamour of a bar, the ceremony of the Wedding, the raucousness of the party. The argument in the mountains is another scene intent upon the people, their humanity and the tensions between them. Suddenly Cimino cuts to a shot of a hunting lodge upon a mountain and his camera follows Michael and Nick as they emerge in the cold grey light of dawn. Choral music rises on the Soundtrack and Walken's silhouette is picked out as he crests a hill and is reflected in a small lake below, his oddly graceful dancer's movements unmistakeable. He and DeNiro are silent on their hunt, which climaxes when DeNiro takes down a deer with his "one shot". We hear that shot and see the deer fall and quiver and die as the music arrives at a crescendo. It is a rare scene of pure natural beauty in the film, and it feels somehow transcendent, blessed by the death of the animal, which seems to presage all of the death and pain to come. A few moments later the film and the characters are in Vietnam, and all is different.

On the basis of The Deer Hunter, Cimino seems like a visionary, more than the equal of other giants of his generation like Coppola and Scorsese. But then he could never sustain such a level, and it seems that the film was a one-off, a uniquely beautiful and perfectly-formed work. The pity of it is that since Heavens Gate, not one of his films has even seemed to have been made by the same man. The best of the four, Year of the Dragon, is an exploitative cop thriller based on an Oliver Stone script and almost parodic in its lack of originality, dredging up of cliches, nastiness and borderline racism. The other three could almost have been made by any journeyman director, so lacking are they in any real personality or sense of vision.

Which raises the question : what could have happened to Cimino? How can such talent simply disappear?

Perhaps its far simpler than that. Perhaps he knew he could never equal The Deer Hunter after his only real attempt, Heavens Gate, almost ruined him. Perhaps he gave up. Who could blame him?

Labels: film