"It is a beast of singular purpose."

My favourite comics creative team - by which I mean ongoing collaboration between a Writer and and Artist - is Stan Lee & Steve Ditko. It has been since I was around 8 years old and I can't see that changing anytime soon unless Grant Morrison starts writing a new Moon Knight title pencilled by John Romita Jr. and inked by Al Williamson with Barry Windsor Smith covers. Lee & Ditko gave us the Amazing Spider-Man and Dr Strange, and they're probably still the Superhero comics I get most pleasure from. Closely following these titans would be a few other creative teams, most of them obviously superb collaborations: Miller & Mazzucchelli, Claremont & Byrne, Moore & Gibbons. At the moment, only Grant Morrison and Frank Quitely even approach any of these other teams - most of the other creators I really admire and enjoy are writer-artists, one man operations. But the team pipping many of these others in my affections is a strange one, who only did a little work together almost 20 years ago: Alan Moore & Alan Davis. But what fine work that was.

Just consider the titles the duo worked on together: Miracleman. D.R & Quinch. Captain Britain. All quite different, all quite superb. I didn't really like D.R. & Quinch at the time. I had an order at my local Newsagents for 2000AD - meaning that every copy I have at home, spanning probably about 12 years, has my surname high on the cover in pencil - and I loved almost all of the long-running and recurring characters. But I liked 2000AD when it was grim and violent. I was less fond of the occasional excursions into satire - unless it was in a Judge Dredd story - and humour back then. D.R. & Quinch was obviously comedy, and though I liked the clean-lined style of Davis' art (which alongside the work of a young Steve Dillon seemed to me to be more obviously influenced by the American artists I myself had a preference for such as John Byrne and George Perez than most artists working in British comics seemed to be, though Davis claims British artists like Frank Hampson as his biggest influences) but not the scripts. Moore never really did his best work for 2000AD, though. Alongside some great "Future Shocks" stories, The Ballad of Halo Jones - with lovely art by Ian Gibson - was probably his best work for the comic, and for me it always seemed uncomfortable in the comics medium. It read like it should have been a big 1000 page Sci-Fi novel, not a serial story in an anthology comic. Skizz barely reads like Moore at all, so conventional and straightforward is its narrative, so modest are its ambitions.

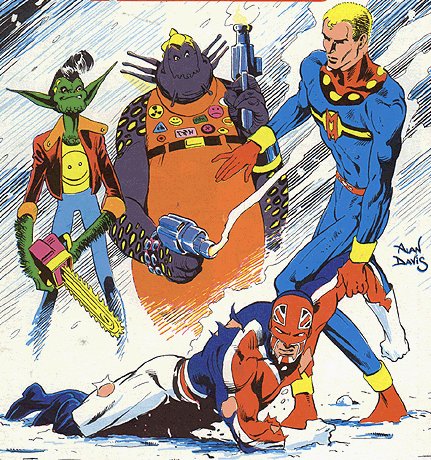

Upon reflection, D.R. & Quinch appears to be both the most and at the same time the least Moore-like example of his work on 2000AD. A sci-fi reading of the National Lampoon characters O.C. & Stiggs (who were made into a middling film by Robert Altman in 1987), it gave him more or less unlimited scope to expand his imagination into and an opportunity to tell various different stories under the same umbrella. But the stories he chose to tell were generally nasty little cartoons wherein his anti-heroes cheerfully, almost obliviously caused havoc. Their first appearance in a Tharg's Time Twisters story opens with these lines from Quinch : "My name's Ernie Quinch, College Student. I like guns and starting fights. My psychiatrist says I'm a psychotic deviant. But that doesn't mean I'm a bad person, right?" Over the course of this story Moore displays both his effortless grasp of Epic storytelling - DR & Quinch create life on Earth and shape the development of humanity basically as part of a longterm plan to get revenge on an enemy - and his mischeivious sense of humour, not always so evident in some of his most famous work. That story also shows that Davis could draw anything - he was as adept at the Alien gatherings as he was at the various single-panel portraits of several historical periods. Later stories were similarly frantic and juvenile, full of crass little jokes, sight-gags and widescreen comic violence. When Moore eventually left, he was replaced by Jamie Delano, which was something of a theme in his UK work with Davis. He has since utterly disowned DR & Quinch, which is a shame, as it reveals a side of his talent rarely seen in the years since.

"Miracleman" is one of the great superhero comics of the 1980s, and its a tribute to its quality to see its influence and reputation surviving after over a decade out of print. The horribly complicated and bitter legal proceedings over ownership look set to ensure the continuation of that situation, which seems sinful (you can find copies of the collections on eBay, each going for a small fortune, and it may just be cheaper to buy the single issues). Moore and Davis collaborated on the series only very briefly, Davis taking over from Gary Leach on art when the series was still being serialized - as "Marvelman" - in "Warrior" magazine. But, just as on Dr & Quinch, Davis had found his style by the time he came to "Miracleman", and was merely sharpening his storytelling from month to month. But it was clear that here was a great Superhero artist, seemingly born to draw countless figures in flight, with a lovely line and superb pacing and staging abilities. He complimented Moore's script perfectly. And Moore's script is the true glory of "Miracleman". It, not the peerless "Watchmen", is the writer's definitive statement on the Superhero genre ("Watchmen" seems to me more a sort of requiem), altough Moore was nowhere near the later highs of the series in the Davis-drawn issues. There he was still introducing characters and themes, and the leap to the big concepts of the Totelbein and Veitch issues seems in retrospect like a massive one. Indeed, the Davis stories can be read as pure Superhero tales, not nearly as revisionist as the series came to be. This suited Davis' pure, mainstream style. But not as much as their other collaboration did.

I always liked Captain Britain as a character, even though I knew he was a bit lame. My introduction to the character came in a two part Marvel Team-Up story uniting him with Spider-Man by Chris Claremont and John Byrne. This was back when he still wore the 70s-era red costume with the big Golden Lion insignia and the Bart Simpson hair, and carried a super-staff of some sort:

I liked the costume back then, liked that he was English, liked that his name was Brian Braddock. The Marvel Team-Up story faced he and Spidey against Arcade and his Murderworld, and the second part was one of my favourite single issues as a kid. I still have the comic, and its been read so many times the covers barely hanging on to the staples. I never saw any of his original run in his own Marvel UK comic, with Claremont scripting and Herb Trimpe art. So the next time I saw Captain Britain, he looked and felt radically different. He was being drawn by Alan Davis, for one thing, and his new costume looked a lot more British and a lot more modern. His staff was gone, too. I couldn't afford to buy the kind of Marvel UK comics he was in back then - it was actually cheaper for me to buy US Marvels - but I browsed them in shops and those stories looked dark and moody to me. When I did get to read them years later, I realised why that was. They had been written by Alan Moore.

Perhaps Moore's greatest gift is an ability to think laterally about characters without losing sight of their core appeal. This has enabled him to successfully rehabilitate numerous titles and characters over the course of his career, from Swamp Thing to the WildCats. He did it on Captain Britain, too, and the Marvel Universe is a far richer place because of his work back then. He took over from writer Dave Thorpe, who had transplanted the character into a parallel universe where Britain has become a repressive, Orwellian dictatorship, ruled over by "Mad" James Jaspers (visually modelled on Terry Thomas) and lumbered him with an impish sidekick, Jackdaw. Moore quickly put an end to the dimension-hopping aspects of the story, though as usual, he saw the potential Thorpe has missed and would later present the Multiverse as a sort of comedic nightmare of conflicting bureaucracies. It was also a convenient means for explaining the origins of any new, wild characters he and Davis came up with. And they came up with plenty.

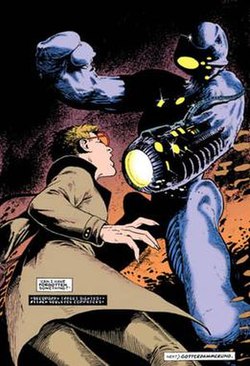

The many members of the Special Executive, for example, a team of inter-dimensional bounty hunters and mercenaries. The various Captain Britains of alternate realities. Megan, who would become Captain Britain's partner, colleague in Excalibur and eventually wife. Perhaps the most memorable is The Fury, the "beast of singular purpose" of the title of this post. A Cybiote monster of steel and flesh created by Jaspers to kill Superheroes, Moore describes it as possessing the "logic of a computer, the intuition of a dog". Davis imagines it as a sort of techno-Golem, featureless but for the distinctive shapes upon its face - its eyes, preumably, though they resemble religious symbols in their primitive, simple symmetry - and its demonic qualities, with its hoof-like feet, its ridged spine, its claw and blaster for hands. The Fury is a terrifying, supremely cool creation, anticipating the similar Terminator by fully a year. Because the thing about the Fury, as Moore and Davis make clear, is that it never stops. It keeps pursuing Captain Britain. It follows him across the Multiverse, crossing dimensions in pursuit. It kills everybody who gets in its way. Moore's descriptions of it are always pitch-perfect: "It runs like a retarded child...a flailing engine of unhindered force, not designed to meet human standards of poise and beauty. But it is very fast, and very strong." It is emotionless, motiveless, merely following its programming. Its climactic battle with the reality-warping Jaspers is awesomely beautiful and epic. Of course, it has been resurrected and used in the Marvel Universe in the years since, though never with the same impact.

Much of Moore's work in the 1980s was obsessed with visions of Dystopian societys - most obviously in "V For Vendetta". "Captain Britain" is no different, as Moore takes Dave Thorpe's work and reruns it through his own sensibility. Jaspers' rise in the alternate reality is repeated in the Britain of the Marvel Universe, and the characters find themselves in a cold, fascist Britain of food-queues and secret police abductions. Moore mixes this with a poetic treatment of Jaspers' crumbling mental state given physical reality by his own superpowers. There is also a sort of smaller scale version of the famed issue of "Watchmen" in which Dr Manhattan mentally timeshifts on the surface of Mars. Except here its all done in two pages and four large panels as the clairvoyant Cobweb deals with sudden altered perceptions. Throughout all this is the steadily improving art of Alan Davis. His character designs are rich and imaginitive and his storytelling and linework only become more acute from issue to issue. By the final chapters, his confidence and assurance are evident, and after a few more years on Captain Britain - in the company of Jamie Delano, who again replaced the departed Moore - he was lured to America to work for DC on "Batman and the Outsiders" (his Neal Adams-esque version of Batman remains one of my favourites). Since then he has worked for both of the big US companies on nearly every one of their major characters, and is now a writer-artist.

The influence of the work Moore and Davis did on Captain Britain is obvious in subtle ways. One of Moore's throwaway ideas in "Captain Britain" was the numbers assigned to the different realities in the multiverse - Brian Braddock's reality, or the reality of the Marvel Universe, of Spider-Man and the X-Men and the Hulk - was number 616. Since the creation of the Ultimate Universe, use of the term "616 Universe" has become commonplace, especially on the Internet, but also within the Marvel Universe itself, leading to some disagreement about it's ultimate origin (Alan Davis, for instance, claims it was coined by Dave Thorpe).

Many of the concepts, characters and situations from Captain Britain became staples of a particular corner of the Marvel Universe when Chris Claremont and Davis revisited them in "Excalibur", which recast Braddock and his supporting cast within the context of the X-Men family. Of course nobody - not even Davis himself, as eventual Writer-Artist on that title - did them quite right, or anywhere near as well as Moore and Davis had done. But then, thats the beauty of the peculiar chemistry leading to a great collaboration. Its mysterious, almost magical. Moore and Davis definitely had it.

Labels: comics

1 Comments:

In case you ain't heard...

Alan Moore is doing his first signing/public appearance for 20+ years at Gosh in February.

If you fancy going I'd go early. I can only imagine it will be fully mental. Can find more details, get tip offs if you're interested.

Post a Comment

<< Home