Michael Reeves died on February 11, 1969, after getting drunk and overdosing on sleeping pills. He had been depressed, insomniac and withdrawn in the preceding months. The coroner's verdict was suicide, but his friends insisted it was an accident despite his recent behaviour. Reeves was considered a great loss to British cinema. Only 25 at the time of his death he had already directed 3 films, one of them - "Witchfinder General"(1968) - a near-masterpiece, and the growth and development of his obvious talent has led to claims that he would have been Britain's answer to Steven Spielberg or a new Orson Welles. The innovative and fascinating ways in which he invested the rote genre material of "the Sorcerers" and "Witchfinder General" with mood, beauty and intensity despite working under major budgetary constraints suggest that these claims may not be entirely without foundation. Instead we are left with a tiny filmography and the tantalising possibilities of what he might have acheived...

Let us imagine Reeves had taken four or five tablets fewer that night in 1969 and woke up the next day, refreshed and reinvigorated after he shed the inevitable hangover. He evaluated his career and his goals. He had always wanted to be a director, ever since his childhood, and here he was. But he had no interest in horror as a genre. It was merely a vehicle for his talent, and it had taken him as far as it could. He had done what he could to treat "Witchfinder General" as if it were a Western rather than a horror film, in any case. A homage to the greats of Classic Hollywood and the B-movie legends he loved: the amazing Western director Budd Boetticher and his own mentor, Don Siegel. He resolved to change his career, to start making the films he was interested in making. He immediately quit working on pre-production of his next film, "The Oblong Box", an Edwardian melodrama/horror. He spent a year or so looking for a new film, collaborating on several scripts, drifting between California and London, mixing with the Laurel Canyon scene and the slowly dissolving Swinging set.

Denied funding for any of the projects in which he was interested, Reeves was forced to return grudgingly to the horror genre. But he insisted upon doing it on his terms. He chose the source material and approved the casting, he wrote the script, he carefully selected each and every collaborator. His adaptation of William Hope Hodgson's 1908 novel "The House On the Borderland" was released in late 1970. Starring Peter O'Toole in the role of the Author of the manuscript, the film was a significant commercial and critical success. Many critics focused upon Reeves confident, stylish direction, his use of suggestion and camera trickery to build suspense and his elaborate marshalling of the special effects sequences which did justice to the more cosmic horror aspects of Hodgon's work. The bleakness of the films ending - in accordance with the ending of the novel - has helped to make it a lasting classic, frequently mentioned near the top of lists of the Greatest Horror films of all time. After that film, Reeves abandoned the genre for over a decade.

Finally granted some commercial clout, and more at home with the newly open and permissive Hollywood which had blossomed in the wake of the success of "Easy Rider" than many directors, Reeves was able to make whatever he liked as his next project. He chose to adapt another novel. He had collaborated with Phillip K. Dick on a script for "The Man In the High Castle", the novelists 1962 alternate history novel of an America under Nazi & Japanese rule, and he began pre-production in 1971. Starring Robert Duvall as Frank Fink, Tuesday Weld as Juliana, James Caan as Joe and Toshiro Mifune as Nobusuke Tagomi, Reeves film is today regarded as one of the key films of the 1970s, even though it flopped catastrophically at the time. Reeves had begun to experiment with lenses and filters between films and "High Castle" is full of evidence of this. Stuffed with visual extremes, character colour-coding, references to the I-Ching and subtle exposition, the film was far too complex and arty for a mainstream audience. Reeves' use of cross-cutting - often so brief as to be almost subliminal - was aggressive and alienating to many viewers. It instantly gained a cult following on U.S. campuses and Weld received an Academy Award Nomination for her work as Juliana. Reeves' stock rose in France, where the film was acclaimed as a masterpiece, and, seeking to escape the collapse of his relationship with folk singer Judee Sill and a worsening heroin habit, he travelled to Paris to undergo a brief period of cold turkey and eventually to make his next film.

"Sticky Fingers"(1972), written, photographed, edited, produced, and directed by Reeves, is an obvious example of a Director taking the auteur theory too seriously. It tells the story of the love triangle between a struggling young actor (played by Reeves' old friend Ian Ogilvy), a model/actress/It-girl (Jacqueline Bisset) and an up-and-coming Rock Star (Terry Reid). Shot in the starkest black and white, mainly using handheld cameras, and full of long dialogue secnes and a couple of extremely sexually explicit sequences, the film was banned in the UK, given an X-Rating in America, and became a massive hit in France. Reeves soundtracked the film with rock and soul music from the period, an approach copied a year later by Martin Scorsese on "Mean Streets". His characters drink, take drugs, dance, have sex and debate in the rooms, streets and parks of a Paris captured as vividly as it has ever been by Reeves' relentlessly mobile camera. The celebrated, much-imitated ending wherein one characters suicide is intercut with the departure of another while the third buries himself in flesh at an orgy deserves its reputation as one of the best shot and cut sequences of the era, and is the logical extension of the cross-cutting technique Reeves had introduced on "The Man in the High Castle". Reeves took the films reception in his homeland hard and coupled with the breakdown in his relationship with Bisset, who had begun to see Francois Truffaut on the set of "Day For Night", he retreated from directing for a few years, only returning in 1975 with a documentary following the lives of a trio of Vietnam veterans upon their return from the War. "Soldiers Three", little-seen at the time, is an incredibly powerful portrayal of lives ruined by politics and of the damage done by combat. Its reticence and the lack of ostentation in the direction makes it play utterly differently to the rest of Reeves' work, to which its a fascinating counterpoint.

His next film was something of a thematic sibling of "Soldiers Three". "Bad Moon Rising" (1977) was the story of the return of two veterans to their Hometown, close to the Mexican border, and how they dealt with the corruption and crime they found newly entrenched there. The veterans - played with convincingly haunted grit by Sam Shepherd and Jon Voight - at first try to reason with the towns new "Owner", Garrett, brilliantly played by Lee Marvin. When that produces no results they resort to violence and after a series of horrifically realistic escalations the War itself is finally re-enacted in a massive battle at Garrett's farm outside town. The film works as both a b-movie action thriller, filled with references to Westerns and War movies (the fact that Shepherd's "Red" has lost an arm is itself a reference to John Sturges' "Bad Day at Black Rock") and an extended metaphor for the War itself. The long scene between Marvin and Carrie Snodgrass (who plays Leah, Voights ex) in which he confesses his lifelong love for her while simultaneously threatening to rape her is a great piece of acting by both performers and an incredibly intense ordeal of a scene, due to the intimacy and resolve of Reeves' direction.

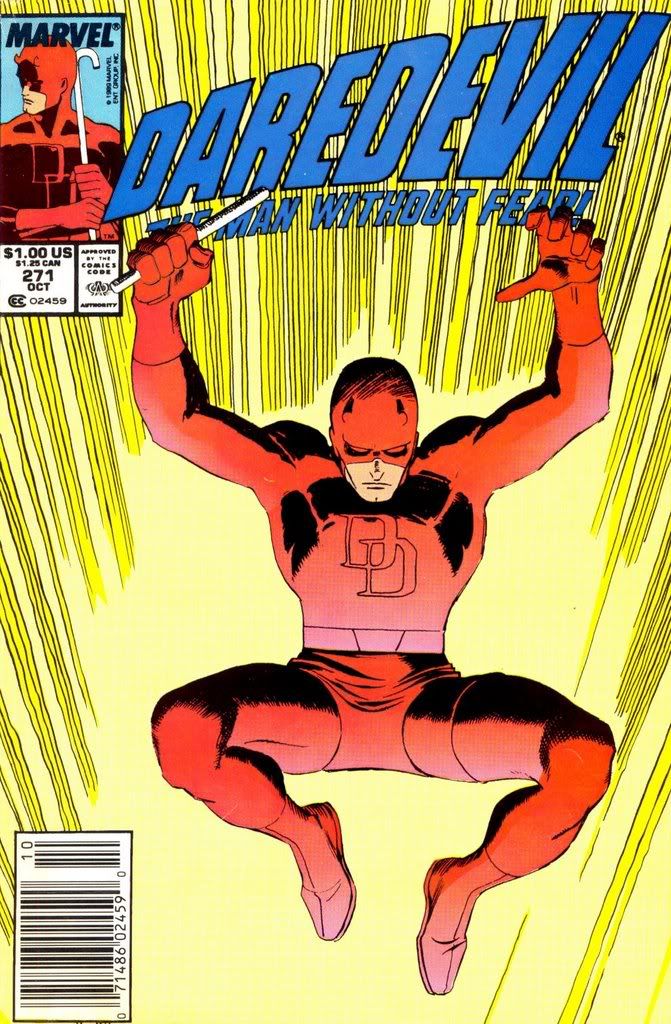

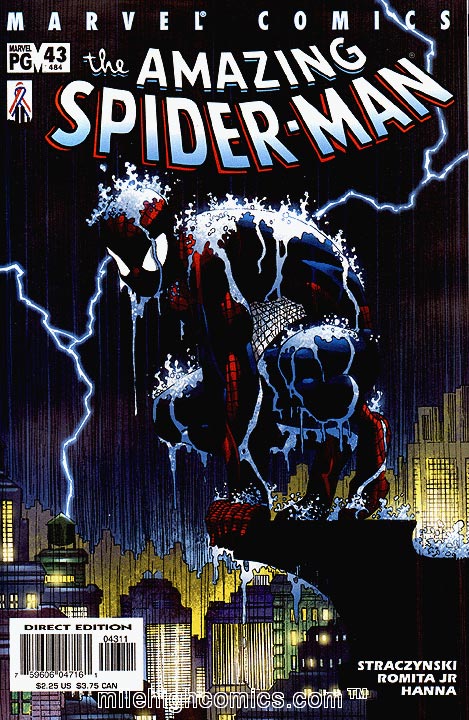

"Bad Moon Rising" was the biggest hit of Reeves' career, and Hollywood, newly interested in Blockbusters after the success of Jaws and Star Wars, hired him to adapt a comic book superhero for a massive film.

"Plastic Man"(1980) starred Elliott Gould in the title role, with Dom DeLuise as Woozy Winks and a young Michelle Pfieffer as Penny. Shot in Italy on massive, elaborately designed soundstages, the film anticipated later films like "Flash Gordon" and "Dick Tracy" in its efforts to render the one-dimensional world of the original comics convincingly in three dimensions. With incredible, uneartly photography by Vittorio Storaro, an insane Ennio Morricone score, no plot to speak of, effects work which has aged quite well, and a charming performance from Gould, "Plastic Man" is not quite the diasaster its reputation suggests. Indeed, if taken in the right spirit, its an engaging, witty slapstick comedy. What it never is, is a Blockbuster Superhero movie, which is what producer Dino DeLaurentis wanted after "Superman" (1978) had done so well commercially. DeLaurentis and Reeves fell out before, during and after shooting, and Reeves was finally locked out of the editing suite. He blamed the resultant incoherence of the cinematic cut of the film on his absence from the edit. The appearance of a Directors Cut on dvd in 2005 indicated that he was correct - his cut is tighter and funnier and many of its zanier pasages play much better than they did in the original version, but it is still a deeply flawed film. Its terrible box office performance and the tales of excess and conflict from the set meant that Reeves did not make another film for five years.

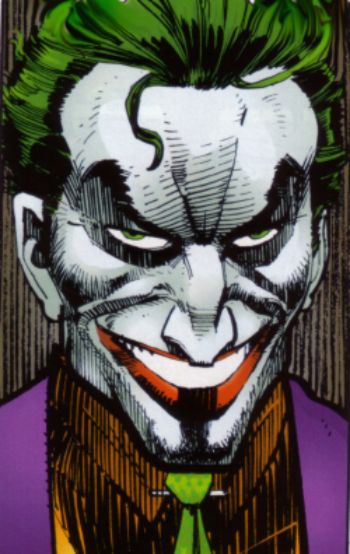

When he returned, he returned to the horror genre. "Baal"(1985), his epic adaptation of Robert McCammon's novel of the rise of a demonically charismatic and destructive Political leader and the efforts of three men - who see his true nature - to stop him was hamstrung by some budgetary restrictions, but is in many ways Reeves' most ambitious and interesting film. It has much to say on the politics and society of the 1980s and seems uncannilly clairvoyant in its usage of Kuwait and Iraq as the seat of a world-changing rise of Islamic Fundamentalism. Its Arctic climax also contains possibly the best action sequence Reeves ever shot, and he draws a fantastic performance from Rutger Hauer as Baal. Maximillian Schell is also brilliant as Virga while Liam Neeson is perfectly cast as Michael, and Jerry Goldsmith's electronic score is among his best and most unsettling work. Reeves used different shooting styles and colour palates for each of his films settings, much as he had done on "The Man in the High Castle" over a decade before. The washed out colours and flat light he uses for the scenes of Baal's time as leader of a Manson-like Californian cult are particularly beautiful and eerie.

Reeves, by this time married to blaxploitation star Vonetta McGee and father to a young daughter, made his next film his most autobiographical to date. "Glad & Sorry"(1987) recalls "Sticky Fingers" in its insistence on the importance of conversation as the basis for drama and narrative, and also in the fluidity of its style. Reeves cast Terence Stamp as an ageing British film director reflecting upon his romantic life as he travels to the funeral of an ex-lover (played in flashbacks by Anouk Aimee). The narrative revolves around his loss of the great love of his life, Nathalie (Julie Christie) to a rival French director, played with sneering arrogance and great humour and charm by Alain Delon. Reeves simplified his stylistic choices on this film and there are many long sequences with unbroken shots and long, slow pans. Stamp spends a lot of time staring into the middle distance, into his past, and his experience and regret are writ in every wrinkle of his still-beautiful face. It may be his greatest ever performance. Each of the flashbacks is a sort of reverie, a series of romanticised moments with beautiful women in a youth that can never be recaptured. Ennio Morricone provides a score played only on piano and cello, a set of variations on a single theme which proves immensely powerful when a full orchestra is brought to bear for the final scenes. The film even suggests a happy ending for Stamp's nameless director with his final encounter with Pam Grier in an airport bar. Ironically, Reeves and McGee divorced before the film was released to great critical notices but little popular success in late 1987.

Again Reeves disappeared from the industry for a few years, apparently writing and painting in his Californian home. He resurfaced in 1992 with "Flicker", a dark conspiracy thriller and alternative history of cinema based upon the cult novel by Theodore Roszak following a young film academic (Matthew Modine) and his research into the work of pre-War hack B-director, Max Castle (played in flashback by Rutger Hauer). The film obviously has trouble articulating the novels claims for the power of Castles work - Reeves makes Castle's films look very much like 1990s advertisments - but it is perfectly paced and always gripping, right until its shattering climax. It is, however, the first film where Reeves' touch is difficult to detect, his individuality somewhat compromised by the demand to make a commercial film. On the promotional circuit for the film, Reeves was not shy about sharing his complaints about the studio and the process with the press, and when pre-production on his proposed next project - a historical epic based on John Milius' screenplay "The Northmen" - ran into trouble, he issued a press statement announcing his retirement from the industry.

Despite frequent rumours that he is collaborating on a screenplay or has been hosting readings of scripts at his house throughout the last decade, Reeves has stuck to his word and made no further directorial contributions to the film industry since that statement in 1995. In that time, his reputation has grown and improved, and his work has been the subject of no less than four books, and one documentary. In 2003 he received a Lifetime achievement Award at the Oscars. He appears in that documentary, interviewed on a balcony overlooking the Pacific, tanned and healthy-looking, discussing his long career with good humour and insight. He has no plans to return to cinema, he says, as if his experience directing "Flicker" has alerted him to its deadly power. He has his painting and his old rock & roll, and he doesn't need any other art.

But the rumours, of course, persist...

*After David Thompson & his James Dean piece....

Labels: film