Manifest Destiny

My Father has given up on fiction. I think he just doesn't really see the point anymore. He still watches movies and television series, but he doesn't read fiction. He's the person who made me such a big reader, probably by example more than anything else, but also through his sermons on what was so great about reading. He borrowed me books - unsolicited - from the library regularly when I was a kid and through the difficult prepubescent years, when I wasn't particularly interested. He was the one who started borrowing Stephen King and James Herbert books for me when I was 12 and 13, and they were the first books I really responded to. They're the reason I went on to study English, in some way, they're the reason I read a book every 10 days or so, on average, they're the reason I found my way to F. Scott Fitzgerald and John Updike and Graham Greene and Richard Yates and every writer I love. Which means that hes the reason.

But I understand his feelings, I think. He is tired of the formulas and the manipulation, tired of investing himself in characters and situations over a long period only to have the writer stiff him in the final chapter. He has a real hatred of an unhappy ending, and one too many novels have been booby-trapped to spring a sudden death or a relationship torn asunder upon him for his liking. A film is two hours of his life and if he dislikes the ending, well thats ok, it was only two hours. A book can be two weeks. It can be hard not to resent those two weeks if they're misspent. So he reads non-fiction. He is a great Hill-walker and nature-lover, and he reads an awful lot of natural history, books about wildlife, nature diaries, farmers diaries etc. But he also likes history and biography and popular science. Just no fiction.

I'm not saying that I feel the same. But I have been reading an increasing amount of non-fiction as I get older. I read a lot of books on cinema, both criticism and history or biography. I read literary biographies and some literary criticism. I read more and more about football. I read some history, and the book I enjoyed most this year was possibly "The Looming Tower" by Lawrence Wright, which is a brilliant account of the birth and development of al-Qaeda and the reasons for the failure of American Intelligence Agencies to stop 9/11. I read it in one day, utterly gripped and fascinated.

One of the reasons I don't read more books is that I read so much other media - newspapers, magazines, the bloody internet. Also, I have come to the end of most of the writers I truly love. I've read everything Fitzgerald wrote, read all of Ian McEwan's books, read all of Richard Ford. The writers I love who still have books I haven't read - well those I have to ration out to myself. One a year, maybe, because eventually they'll all be gone. Discovering new ones is more difficult than discovering unseen directors or new music, again because books take so much personal and temporal investment. I just don't have the time.

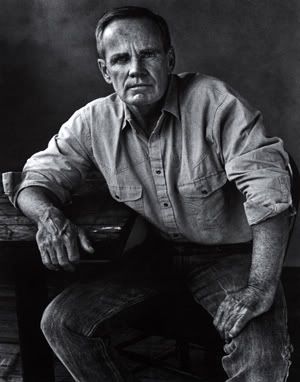

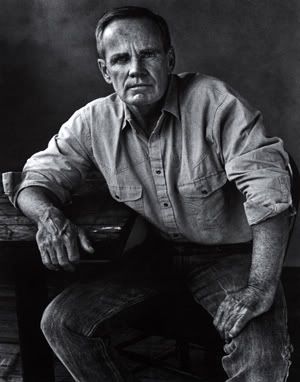

But then occasionally I'll read a novel and it knocks me off my feet and makes me see the power of great fiction all over again. "The Road" by Cormac McCarthy is just such a novel. McCarthy has long been a personal favourite, but recently he's been releasing books at an unprecedented rate. Having written just five books in the two decades between 1965 and 1985, he has just published two in three years. While 2005's "No Country for Old Men" was a dazzling chase thriller set in McCarthy country along the US-Mexican border in the 1980s ( a movie of which, adapted by the Coens and starring Tommy Lee Jones and Javier Bardem, is due in late 2007), "The Road" is a sort of post-apocalyptic fable. It follows the long journey of a father and his son through a ravaged, destroyed America following some unspecified but presumably Nuclear cataclysm. The man and boy are following the highway through a dead landscape, heading South to the Ocean, desperate to find something living in what they hope will be still warmer climes. They scavenge what food they can find in abandoned houses and shops, for there are no more living animals and no plant-life still growing. The weather attacks them ceaselessly and ash blows at them off the ruined countryside as they go. They are terrified of the bands of cannibalistic marauders - "bloodcults" - roaming the country, picking off lone survivors, and the novel features a couple of almost unbearably gripping scenes as they encounter such men.

The father tries always to buoy his sons spirits. They are the good guys, he tells him, they are carrying the fire. All the while he must fight his own hopelessness and despair, the suicidal impulses which make his possession of a revolver loaded with a single bullet - more to end the boy's life in the event of capture by the marauders than for defence - a dangerous necessity, and also struggling with his memories of life before the catastrophe and of the boy's mother. They trudge on down the road, through ghost towns, skirting skeletal cities, finding shelter where they can, trying to stay dry and healthy. Their bond - the boy's questions and fear and love and trust, the fathers exhaustion and tenderness and pride and sorrow - are beautifully evoked by McCarthy in the spare conversations they have as they walk or at night as they huddle together for warmth.

The novel - like much of McCarthy's work - sustains a mood of palpable tension and dread throughout. Its action is repetitive, as are its descriptions of the bleak graveyard that the world has become. But McCarthy's descriptive language is always precise, always evocative - "By day the banished sun circles the earth like a grieving mother with a lamp." - and its cumulative effect, when combined with the characterisation of the man and boy, is extraordinarily moving. Having moved away from the polysyndetonic syntax he used in the Border trilogy (the novels "All the Pretty Horses", "the Crossing" and "Cities of the Plain") his language here, as in "No Country for Old Men", is plainer, punchier, his sentences frequently short and sparse. Somehow, despite the slight stylistic shift, he retains the timeless, quasi-biblical tone his work has employed since "Blood Meridian".

While "The Road" recalls many other works and films set in post-apocalyptic landscapes, from Harlan Ellison's "A Boy & His Dog" to the Mad Max films and The Postman and even the work of George R Romero, McCarthy's unique voice and the absence of anything really resembling a plot give it an identity unlike anything I have really encountered before. In terms of an almost domestic approach to apocalypse( "The Road" is filled with details of practicalities - how they eat, what they use to keep warm, where they shelter), the sensibility is perhaps closest to Michael Haneke's The Hour of the Wolf, but McCarthy's work is far more mythic and poetic than the cold world of Haneke's film.

McCarthy is generally celebrated for the quality of his exquisite prose, and is unarguably one of the greatest living American novelists. "The Road" reads almost like the pinnacle of his work. Perhaps the simplest and purest book he has written, it takes something from each of his other novels. The pitch-black tone of barbarity is familiar from his first three novels, the appalling and terrifying violence of men in a lawless world recalls the killers rampaging through Indian villages in "Blood Meridian", the tenderness and emotion and focus upon landscape seem to have come from his Border trilogy, and the mature and regretful ruminations of the main character suggest the Sheriff's philosophical passages in "No Country For Old Men".

"The Road" also feels like a novel only a mature writer could have written. McCarthy is 73, and his last few books have all dealt with the shadow of death and mortality. He is never sentimental but his book is heavy with an awareness of what is important in life, the lack of limits of parental love,with regret and mourning for the beauty of the world. If in the past he has been compared - with good reason - to Hemingway, Melville and Faulkner, here the most relevant literary comparison is with Beckett. This book has his fearlessness, his refusal to blink in the face of despair. It is also moving, exciting and thrillingly beautiful. It is one reason why my father is wrong to have given up on fiction.

Flags of Our Fathers is a fiction based on a non-fiction book, and accordingly, it makes a convincing argument for the worth of historical reality in our portrayals of the past. Like Cormac McCarthy, Clint Eastwood is a genuine American artist, and one whose work only seems to be developing in quality and complexity as he gets older. He has always been a capable, competent director. If that seems to be damning him with faint praise, well thats because it is. But his charisma and star quality as an actor has always been so inexorably bound up in his work as a director that it has been difficult in the past to judge his acheivements behind the camera. Would any of the films he has directed and starred in work half so well with any other actor in the lead? Take, for example, Unforgiven, his most critically acclaimed and successful Western as director. It works so well because of the genre baggage Eastwood the actor carries in that familiar craggy face, the expectations an audience has of his archetypal hero in any film with horses and hats and six-shooters. It is obviously a well-shot film, and Eastwood as a director understands that particular genre as well as any practitioner ever has, so that Unforgiven is perfectly paced and dramatically satisfying. But there has always been a slight sense that he was an easy director to respect and admire but a hard one to love. He is too old-fashioned, too workmanlike. He wrested control of The Outlaw Josey Wales from its writer and original director Phil Kauffman and, much as I love the film for its many great moments and its odd communal happy ending, it makes me wonder how much more interesting a film it would be if Kauffman had remained in charge. Of the two directors Unforgiven is dedicated to, Don Siegel and Sergio Leone, it seems clear that Eastwood learned more from the former. His camera always seems to be in the right place in order to advance his narrative, but not necessarily the place which would make for the most interesting or beautiful shot. His editing is clean, his storytelling clear and without any flab. This is all similar to Siegel, who made some of the tightest, tautest, most efficient genre films in Hollywood in the 50s and 60s. Leone instead embraced the flab, and saw the beauty in turning his camera upon the quiet moments, saw that sometimes a beautiful composition is enough for its own sake, something that Eastwood never seemed capable of seeing.

Until, perhaps, his elderly years. Eastwood is 76 now, his last three films are perhaps the strongest run in his entire directorial career, and if early reviews of his companion piece to flags of Our Fathers, Letters from Iwo Jima, are to believed, this run looks set to continue. In 2003 he directed Mystic River from Denis Lehane's novel, and though in the past his work has not shied away from scrutinising the darker side of life - and of his own screen persona, in films like Tightrope, the Beguiled and even the Dirty Harry series - here his gaze seems fiercer somehow, his attraction to the material more obvious. There is an ambiguity in the conclusion of Mystic River absent from his earlier work, even in the artier films, like Bird and White Hunter, Black Heart. This ambiguity extends forward into Million Dollar Baby, where the audience must decide for itself how it feels about Eastwood's character damning himself for somebody he loves. Flags of Our Fathers is another ambiguous, complex film. It borrows the tools of non-fiction and documentary : much of it is told is voiceover, excerpted from interviews conducted by the son of one of the protagonists. Hence the narrative shifts around, from viewpoint to viewpoint, through different time periods and places and perspectives. This approach is almost essay-like, and indeed Eastwood does appear to be crafting an argument. The ambiguity lies in what he may be arguing. The film obviously works as an anti-War piece, with its Saving Private Ryan-like scenes of young soldiers riddled with bullets and pounded by explosions on beaches and in foxholes, and also in the post-War scenes which follow the fortunes of the shellshocked "Heroes" of Iwo Jima. But it also explicitly celebrates the values of men in combat, friendship and honour and loyalty, and states that men fight and die for their comrades and not their countries.

While we have seen all of this before, very recently in the case of Spielberg's film, and in Band of Brothers, and in The Thin Red Line, Eastwood's approach is fresh and different enough to make it interesting again. Though his battle scenes have the now customary mix of washed out colour and gory blood-spilling, they are not directed with quite the same intuitive genius for action and spectacle evident in Saving Private Ryan or with Malick's lyrical eye for beauty. So the film really comes alive in the quieter scenes, especially the passages set in wartime America, which the young soldiers must tour in an effort to sell Warbonds to fund the conflict. These sequences recall James Jones' "Whistle", the concluding book of the trilogy which included "From Here to Eternity" and "The Thin Red Line". The soldiers face surreal re-enactments - complete with explosions and simulated gunfire - and spontaneous applause in public as they try to deal with the fact that they are still alive while many of their friends are not. Their numb and bemused faces betray them in scene after scene. One of them collapses inward upon himself, drinking and brawling his way through the tour. The insensitivity and ignorance of the general public is vividly portrayed, but Eastwood never takes any cheap shots or makes any easy judgements. His film suggests that history is too complex for such trite summations. One of his characters, though haunted and guilt-ridden by his experiences of the War, raises a family, runs a business, and lives a long life without ever again speaking of it. When he does talk to his son about it, on his deathbed, he recalls swimming with his friends off Iwo Jima, between battles. He chooses to share a rare moment of happiness amidst the bloodshed and slaughter, to concentrate on the human in the middle of so much inhumanity. This is an attitude you feel Eastwood, like Cormac McCarthy, understands perfectly.

But I understand his feelings, I think. He is tired of the formulas and the manipulation, tired of investing himself in characters and situations over a long period only to have the writer stiff him in the final chapter. He has a real hatred of an unhappy ending, and one too many novels have been booby-trapped to spring a sudden death or a relationship torn asunder upon him for his liking. A film is two hours of his life and if he dislikes the ending, well thats ok, it was only two hours. A book can be two weeks. It can be hard not to resent those two weeks if they're misspent. So he reads non-fiction. He is a great Hill-walker and nature-lover, and he reads an awful lot of natural history, books about wildlife, nature diaries, farmers diaries etc. But he also likes history and biography and popular science. Just no fiction.

I'm not saying that I feel the same. But I have been reading an increasing amount of non-fiction as I get older. I read a lot of books on cinema, both criticism and history or biography. I read literary biographies and some literary criticism. I read more and more about football. I read some history, and the book I enjoyed most this year was possibly "The Looming Tower" by Lawrence Wright, which is a brilliant account of the birth and development of al-Qaeda and the reasons for the failure of American Intelligence Agencies to stop 9/11. I read it in one day, utterly gripped and fascinated.

One of the reasons I don't read more books is that I read so much other media - newspapers, magazines, the bloody internet. Also, I have come to the end of most of the writers I truly love. I've read everything Fitzgerald wrote, read all of Ian McEwan's books, read all of Richard Ford. The writers I love who still have books I haven't read - well those I have to ration out to myself. One a year, maybe, because eventually they'll all be gone. Discovering new ones is more difficult than discovering unseen directors or new music, again because books take so much personal and temporal investment. I just don't have the time.

But then occasionally I'll read a novel and it knocks me off my feet and makes me see the power of great fiction all over again. "The Road" by Cormac McCarthy is just such a novel. McCarthy has long been a personal favourite, but recently he's been releasing books at an unprecedented rate. Having written just five books in the two decades between 1965 and 1985, he has just published two in three years. While 2005's "No Country for Old Men" was a dazzling chase thriller set in McCarthy country along the US-Mexican border in the 1980s ( a movie of which, adapted by the Coens and starring Tommy Lee Jones and Javier Bardem, is due in late 2007), "The Road" is a sort of post-apocalyptic fable. It follows the long journey of a father and his son through a ravaged, destroyed America following some unspecified but presumably Nuclear cataclysm. The man and boy are following the highway through a dead landscape, heading South to the Ocean, desperate to find something living in what they hope will be still warmer climes. They scavenge what food they can find in abandoned houses and shops, for there are no more living animals and no plant-life still growing. The weather attacks them ceaselessly and ash blows at them off the ruined countryside as they go. They are terrified of the bands of cannibalistic marauders - "bloodcults" - roaming the country, picking off lone survivors, and the novel features a couple of almost unbearably gripping scenes as they encounter such men.

The father tries always to buoy his sons spirits. They are the good guys, he tells him, they are carrying the fire. All the while he must fight his own hopelessness and despair, the suicidal impulses which make his possession of a revolver loaded with a single bullet - more to end the boy's life in the event of capture by the marauders than for defence - a dangerous necessity, and also struggling with his memories of life before the catastrophe and of the boy's mother. They trudge on down the road, through ghost towns, skirting skeletal cities, finding shelter where they can, trying to stay dry and healthy. Their bond - the boy's questions and fear and love and trust, the fathers exhaustion and tenderness and pride and sorrow - are beautifully evoked by McCarthy in the spare conversations they have as they walk or at night as they huddle together for warmth.

The novel - like much of McCarthy's work - sustains a mood of palpable tension and dread throughout. Its action is repetitive, as are its descriptions of the bleak graveyard that the world has become. But McCarthy's descriptive language is always precise, always evocative - "By day the banished sun circles the earth like a grieving mother with a lamp." - and its cumulative effect, when combined with the characterisation of the man and boy, is extraordinarily moving. Having moved away from the polysyndetonic syntax he used in the Border trilogy (the novels "All the Pretty Horses", "the Crossing" and "Cities of the Plain") his language here, as in "No Country for Old Men", is plainer, punchier, his sentences frequently short and sparse. Somehow, despite the slight stylistic shift, he retains the timeless, quasi-biblical tone his work has employed since "Blood Meridian".

While "The Road" recalls many other works and films set in post-apocalyptic landscapes, from Harlan Ellison's "A Boy & His Dog" to the Mad Max films and The Postman and even the work of George R Romero, McCarthy's unique voice and the absence of anything really resembling a plot give it an identity unlike anything I have really encountered before. In terms of an almost domestic approach to apocalypse( "The Road" is filled with details of practicalities - how they eat, what they use to keep warm, where they shelter), the sensibility is perhaps closest to Michael Haneke's The Hour of the Wolf, but McCarthy's work is far more mythic and poetic than the cold world of Haneke's film.

McCarthy is generally celebrated for the quality of his exquisite prose, and is unarguably one of the greatest living American novelists. "The Road" reads almost like the pinnacle of his work. Perhaps the simplest and purest book he has written, it takes something from each of his other novels. The pitch-black tone of barbarity is familiar from his first three novels, the appalling and terrifying violence of men in a lawless world recalls the killers rampaging through Indian villages in "Blood Meridian", the tenderness and emotion and focus upon landscape seem to have come from his Border trilogy, and the mature and regretful ruminations of the main character suggest the Sheriff's philosophical passages in "No Country For Old Men".

"The Road" also feels like a novel only a mature writer could have written. McCarthy is 73, and his last few books have all dealt with the shadow of death and mortality. He is never sentimental but his book is heavy with an awareness of what is important in life, the lack of limits of parental love,with regret and mourning for the beauty of the world. If in the past he has been compared - with good reason - to Hemingway, Melville and Faulkner, here the most relevant literary comparison is with Beckett. This book has his fearlessness, his refusal to blink in the face of despair. It is also moving, exciting and thrillingly beautiful. It is one reason why my father is wrong to have given up on fiction.

Flags of Our Fathers is a fiction based on a non-fiction book, and accordingly, it makes a convincing argument for the worth of historical reality in our portrayals of the past. Like Cormac McCarthy, Clint Eastwood is a genuine American artist, and one whose work only seems to be developing in quality and complexity as he gets older. He has always been a capable, competent director. If that seems to be damning him with faint praise, well thats because it is. But his charisma and star quality as an actor has always been so inexorably bound up in his work as a director that it has been difficult in the past to judge his acheivements behind the camera. Would any of the films he has directed and starred in work half so well with any other actor in the lead? Take, for example, Unforgiven, his most critically acclaimed and successful Western as director. It works so well because of the genre baggage Eastwood the actor carries in that familiar craggy face, the expectations an audience has of his archetypal hero in any film with horses and hats and six-shooters. It is obviously a well-shot film, and Eastwood as a director understands that particular genre as well as any practitioner ever has, so that Unforgiven is perfectly paced and dramatically satisfying. But there has always been a slight sense that he was an easy director to respect and admire but a hard one to love. He is too old-fashioned, too workmanlike. He wrested control of The Outlaw Josey Wales from its writer and original director Phil Kauffman and, much as I love the film for its many great moments and its odd communal happy ending, it makes me wonder how much more interesting a film it would be if Kauffman had remained in charge. Of the two directors Unforgiven is dedicated to, Don Siegel and Sergio Leone, it seems clear that Eastwood learned more from the former. His camera always seems to be in the right place in order to advance his narrative, but not necessarily the place which would make for the most interesting or beautiful shot. His editing is clean, his storytelling clear and without any flab. This is all similar to Siegel, who made some of the tightest, tautest, most efficient genre films in Hollywood in the 50s and 60s. Leone instead embraced the flab, and saw the beauty in turning his camera upon the quiet moments, saw that sometimes a beautiful composition is enough for its own sake, something that Eastwood never seemed capable of seeing.

Until, perhaps, his elderly years. Eastwood is 76 now, his last three films are perhaps the strongest run in his entire directorial career, and if early reviews of his companion piece to flags of Our Fathers, Letters from Iwo Jima, are to believed, this run looks set to continue. In 2003 he directed Mystic River from Denis Lehane's novel, and though in the past his work has not shied away from scrutinising the darker side of life - and of his own screen persona, in films like Tightrope, the Beguiled and even the Dirty Harry series - here his gaze seems fiercer somehow, his attraction to the material more obvious. There is an ambiguity in the conclusion of Mystic River absent from his earlier work, even in the artier films, like Bird and White Hunter, Black Heart. This ambiguity extends forward into Million Dollar Baby, where the audience must decide for itself how it feels about Eastwood's character damning himself for somebody he loves. Flags of Our Fathers is another ambiguous, complex film. It borrows the tools of non-fiction and documentary : much of it is told is voiceover, excerpted from interviews conducted by the son of one of the protagonists. Hence the narrative shifts around, from viewpoint to viewpoint, through different time periods and places and perspectives. This approach is almost essay-like, and indeed Eastwood does appear to be crafting an argument. The ambiguity lies in what he may be arguing. The film obviously works as an anti-War piece, with its Saving Private Ryan-like scenes of young soldiers riddled with bullets and pounded by explosions on beaches and in foxholes, and also in the post-War scenes which follow the fortunes of the shellshocked "Heroes" of Iwo Jima. But it also explicitly celebrates the values of men in combat, friendship and honour and loyalty, and states that men fight and die for their comrades and not their countries.

While we have seen all of this before, very recently in the case of Spielberg's film, and in Band of Brothers, and in The Thin Red Line, Eastwood's approach is fresh and different enough to make it interesting again. Though his battle scenes have the now customary mix of washed out colour and gory blood-spilling, they are not directed with quite the same intuitive genius for action and spectacle evident in Saving Private Ryan or with Malick's lyrical eye for beauty. So the film really comes alive in the quieter scenes, especially the passages set in wartime America, which the young soldiers must tour in an effort to sell Warbonds to fund the conflict. These sequences recall James Jones' "Whistle", the concluding book of the trilogy which included "From Here to Eternity" and "The Thin Red Line". The soldiers face surreal re-enactments - complete with explosions and simulated gunfire - and spontaneous applause in public as they try to deal with the fact that they are still alive while many of their friends are not. Their numb and bemused faces betray them in scene after scene. One of them collapses inward upon himself, drinking and brawling his way through the tour. The insensitivity and ignorance of the general public is vividly portrayed, but Eastwood never takes any cheap shots or makes any easy judgements. His film suggests that history is too complex for such trite summations. One of his characters, though haunted and guilt-ridden by his experiences of the War, raises a family, runs a business, and lives a long life without ever again speaking of it. When he does talk to his son about it, on his deathbed, he recalls swimming with his friends off Iwo Jima, between battles. He chooses to share a rare moment of happiness amidst the bloodshed and slaughter, to concentrate on the human in the middle of so much inhumanity. This is an attitude you feel Eastwood, like Cormac McCarthy, understands perfectly.